STORIES IN STONE

Ernestina Fisher Coult’s Journey

Anti-immigrant sentiment remained strong in newly named Old Lyme when the Fisher family arrived from Prussia, now part of Germany. Traveling with few possessions, the group of ten, including an infant son, boarded a relatively small merchant ship, the Isaac Allerton, in Hamburg with 246 other passengers. After a long voyage, likely in cramped quarters with poor food, limited ventilation, and crude sanitary conditions, the ship reached New York harbor in October 1854.

Robert McCurdy Lord, raised in his family’s comfortable home on today’s Lyme Street, had inquired two years earlier in an essay written while a student at Yale, “Is foreign immigration beneficial to our country?” Lord argued that, “No country ever has ever experienced such an influx of foreign population as our own.” He noted that the foreign-born arrived “destitute and impoverished, frequently afflicted with loathsome diseases,” and that they “crowd our hospitals alms-houses and dispensaries” and “increase the already immense burden of domestic pauperization.”

Like Irish immigrants who found work in Lyme in the 1850s, members of the Fisher family were employed as farm laborers and domestic servants. Ernestina, in her mid-teens, was hired by the family of William E. Coult. Her parents and some of her siblings later sought greater opportunities and moved to Oregon. They urged Ernestina to follow them, but William and his mother Mary Marvin Coult persuaded her to continue her service in their home and large farm on Neck Road.

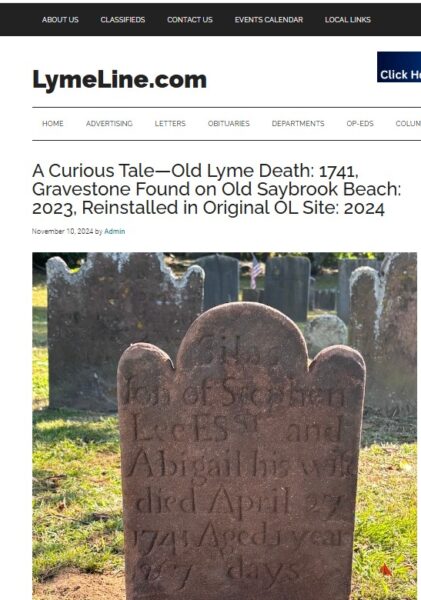

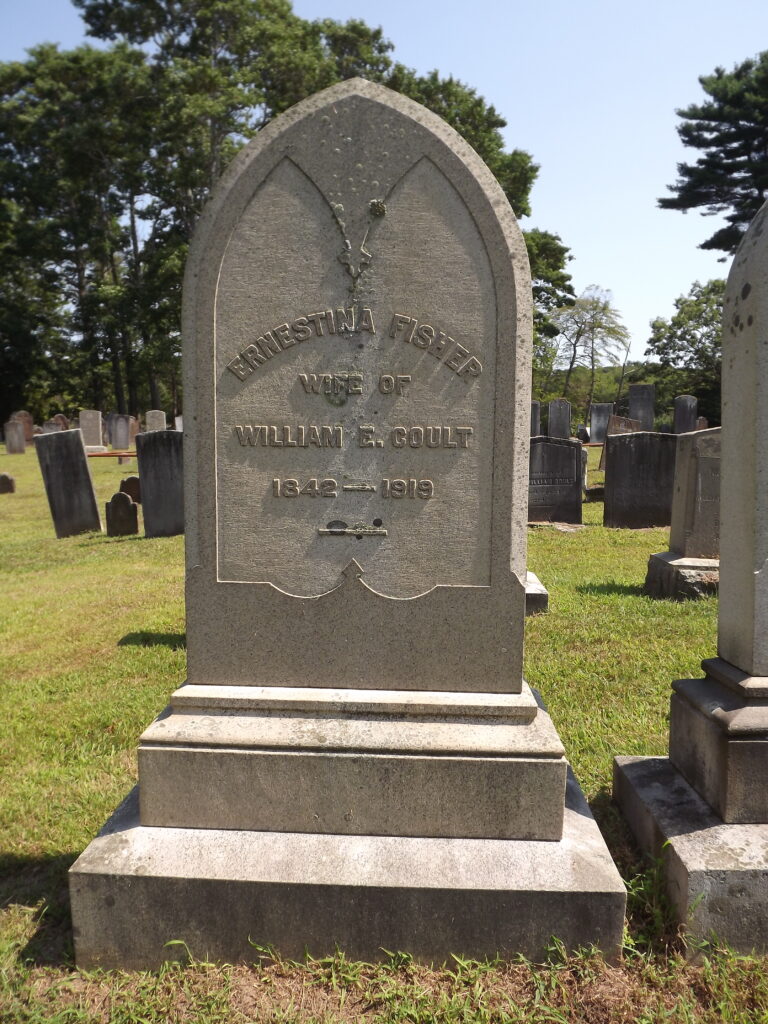

When Ernestina reached the marriageable age of 21 in 1863, she joined the Congregational Church and soon became the wife of William Coult, age 66. A respected school teacher and treasurer of the church, Coult had never married, and over the next 10 years they had three daughters and a son. When William died in 1876, Ernestina became head of the household. Fully accepted by Old Lyme’s established families, she managed the farm and applied her energy and financial resources to educate their children in the town’s private schools. She remained actively engaged in the community until her final illness in 1919, and a substantial monument in Duck River Cemetery commemorates her life and her journey.

— Charles Beal

Gravestones in Duck River Cemetery have stories to tell about the lives of those who passed before us in the Lyme region and the events that shaped the development of a Connecticut town, distinguished by its prominent lawyers and ministers, its shipbuilding and maritime trade, its architecture and scenic landscape, and its contributions to education, conservation, and the arts.